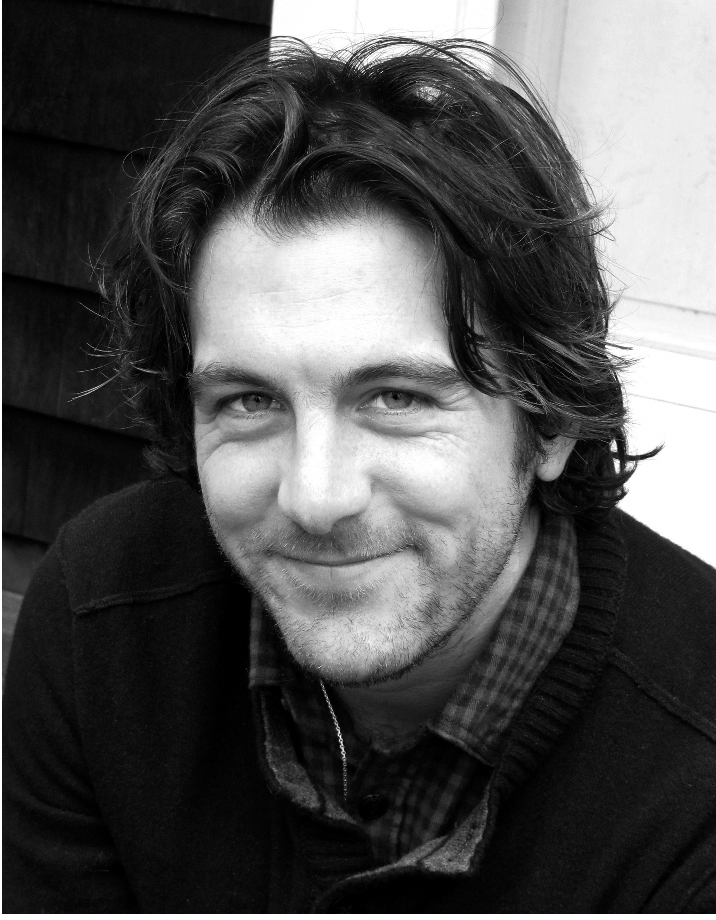

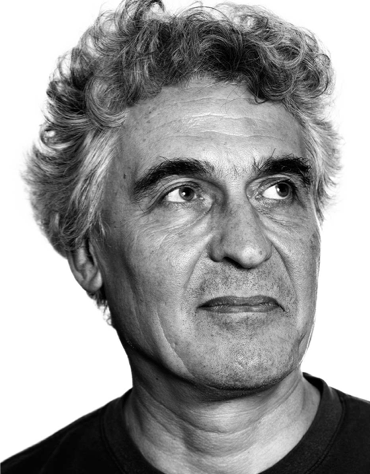

Managing Editor Eric Smith spoke to Will Schutt about Italian-Swiss poet Fabio Pusterla, whose poems, translated by Schutt, appeared in our Spring 2019 issue. Schutt, author of the 2012 Yale Series of Younger Poets award-winning collection Westerly, discusses Pusterla’s poetic lineage, ambulation in poetry, and the effect of translation on his own work.

SR: Situate for us Fabio Pusterla’s work: in the larger context of Italian literature, but also within his own circumstances as someone born in, and living and working on, the border between Switzerland and northern Italy. Do you see the circumstances of his life putting pressure of any kind on his work?

WS: I feel funny “situating” Pusterla; should the translator always have the last word? But here goes: Pusterla is a major contemporary poet in Italy. He has written eight books of poetry and a few collections of essays, and he has also translated several volumes of poetry from the French and Portuguese, in particular the work of the Francophone Swiss poet Philippe Jaccottet.

On the one hand, you can trace a lineage to northern Italian and Swiss poets such as Eugenio Montale, Giorgio Orelli, and Vittorio Sereni. There is a tendency in Pusterla’s poetry to focus on humble things—and humble lives—that recalls the early twentieth-century poet Giovanni Pascoli. Like Pascoli and Montale, Pusterla takes great pleasure in naming the natural world: screes, copal, catchfly. While the emotional sources of his poems can be hard to pin down, the landscape they inhabit is almost invariably the austere Swiss Alps.

On the other hand, his idiom is modern and his subjects usually of global concern. He writes about environmental degradation, consumerism, media saturation, and life on the abrupt edge—to get to the second half of your question, and borrow a wonderful phrase used by ornithologists and more richly adopted by the late Stanley Plumly to think about poetry. I believe the circumstances of his life, living on the border between Switzerland and Italy, provide Pusterla with one way to explore ideas about marginality, social purpose, and mainstream culture in the twenty-first century.

SR: What is it about Pusterla's work—or these poems, which appear in one of his more recent collections, Argéman—that asked (maybe demanded) to be translated?

WS: I love Fabio’s range of tone. He can be mordant and tender, public and intimate, restrained and outraged, sometimes all in the same poem. That variety is on display in both poems that appear in the Sewanee Review; in, for instance, the surprising contrast between the children’s games and the turn-on-a-dime rebuke from the woman in “History of the Language.” The poem starts local and ends historical.

Fabio is a great walker. At least many of his poems give me the impression he is. They don’t rush off with a specific purpose yet brave their environment, and gradually arrive at something that feels like a lucked-into destination. In Fabio’s prose poem “Fog,” this apparent aimlessness, alluded to in the title, dictates the form and becomes, paradoxically, its center of gravity. The poem is deeply aware of what it means to be at the mercy of the right margin: the dangers inherent in jumping the fence, the dangers inherent in demanding more than your fair share.

SR: You're a poet yourself; what kinds of pressure does translating the work of another poet put on your work, or your practice?

WS: You like the word pressure! Translation in that sense doesn’t feel like pressure; it is a relief from writing my own poems. I’m also grateful for the opportunity it affords to sidestep the atmosphere of the current moment in American poetry. Or rather, to think about the current moment in American poetry, and how it departs from and/or mirrors the larger concerns of poetry in general. More importantly—and plenty of other people have said this before me, but it holds water—translating necessitates reading deeply, necessitates dwelling on another poet’s choices: their tone, their diction, their syntax, their line breaks. And then gradually you begin translating, which is to say, writing your own poem out of that poem, because the target language always has other designs and demands that you must respond to. I’m sure that has had an effect on my own practice. It has probably slowed me down. Translation also reminds me of the value of clarity in poetry—even when your poems wander in a fog.