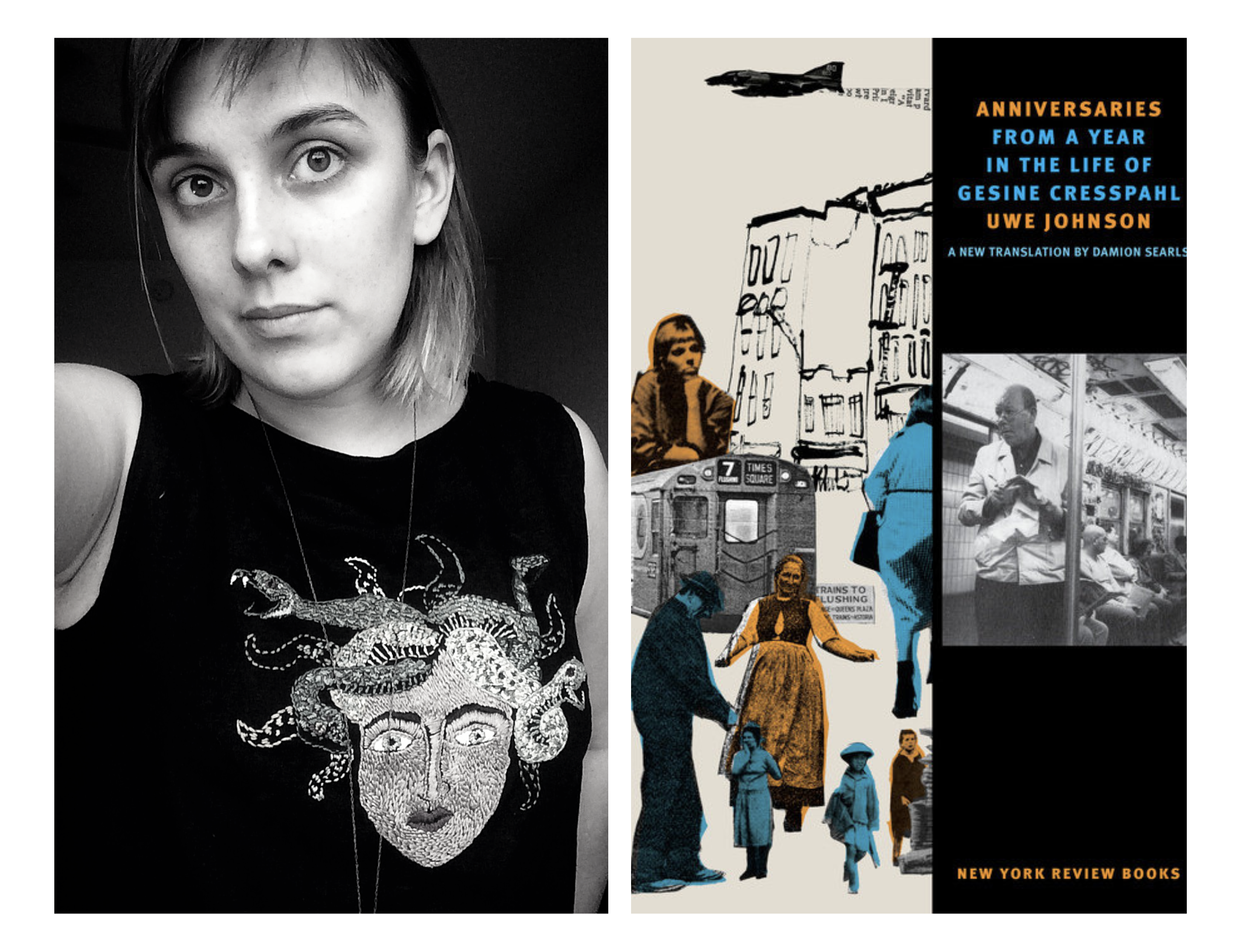

For our Marginalia web feature, we ask writers to introduce us to their favorite works of literature by way of a short piece of prose. This week, Celia Bell, author of the haunting and haunted story “Family Oracle” from our Summer 2019 issue, examines a passage from Anniversaries by Uwe Johnson.

When I was in college or just out of it, I used to babysit for a couple who lived on Ninety-Second Street and Riverside Drive in Manhattan. The husband was a German art dealer, who I shocked one night by saying that I didn’t like Tolstoy. He told me that I should keep that a secret, and then he softened a little and pulled a book from the shelf behind my head and said, “You should take this and read it. It’s by a German author who used to live just a few blocks away from here, on Ninety-Sixth Street, in the ’60s. You’ll like it. There’s a chapter for every day of the year.”

The book was the first English translation of Anniversaries by Uwe Johnson. It is on my bookshelf at this moment, the cover a little worse for the wear. It is the only book I can remember deliberately stealing.

That book was only a partial translation, the first volume of a 1300-page novel, which until last year had never appeared in English in its entirety. The novel spans one year in the life of Johnson’s heroine, Gesine Cresspahl, from August 1967 to August 1968—three hundred sixty-five chapters, three hundred sixty-five days that are happy or tragic or unremarkable, punctuated by the routines of work and reading the paper. Gesine, an immigrant from East Germany, now a single mother in Manhattan, is obsessed with the American conflict in Vietnam and the larger context of the Cold War. She is horrified and disillusioned with America, in whose policies of racial segregation at home and conquest abroad she sees echoes of the violence and repression that shaped her childhood in Germany, but in the face of which she feels that all of her actions are futile.

In the face of her political helplessness, Gesine mines her memories of growing up in Nazi Germany, telling her daughter Marie about the uneasy acquiescence with which her hometown viewed the rise of the Nazis, her parents’ inadequate resistances and unhappy collaboration, and her own coming of age under Soviet-controlled East Germany.

Now I could see the dead woman on the guest cot, a short and thinner figure than in real life, in a limp and helpless position, her head already half wrapped in hair. The figure was wearing a brown dress I didn’t recognize. I’ve never liked wearing brown.

I knew the next thought but I just couldn’t think it: I was dead, ever since I’d heard the elevator if not longer, probably since the night before last. I could still tell that much. But now I had to go view the body before I lost all my strength, and be the body.

The child told me to get to work. Marie was standing at the gray window, in the morning, at dawn, and holding up a handkerchief by both ends to block the meager light. The handkerchief was strangely square and unusually bright. I went and stood carefully behind her. Pictures appeared on a radiant patch of light between Marie’s fingers—never before seen, never before photographed, in cold, precise colors:

Lisbeth Cresspahl in her coffin

Lisbeth Papenbrock, six years old, with long hair, lying as though floating, in profile

the barn before it burned down

a chicken pecking off a strawberry from beneath

the Baltic from a very fast very long flyover

—Uwe Johnson, Anniversaries

The passage above describes a dream. “Yesterday,” Gesine writes earlier in the chapter, “I gave dying a try.” She’s split off from herself, seeing her brown dress (the color of the SA paramilitary uniforms), her body lying prone the way her mother, Lisbeth (who died under dubious circumstances during the war), lay her in coffin. Is she the body on the cot or the eye that observes, the dead woman or her mourner?

The fracturing of stable identity is a hallmark of Johnson’s novel, which Gesine narrates sometimes in first person and sometimes in third. Dreaming, she must both “view the body” and “be the body,” an impossible unity of perception and experience. Never before seen, never before photographed. The novel shatters into incomplete, broken lines, its narrator no longer interested in a complete, orderly description of memory.

Of her own dead, Gesine asks: Did you do the best you could? She will ask herself the same question, and come up perpetually short. Instead, there is the inassimilable unseen: the coffin, the chicken, her mother’s hair, all of which are locked away in the world of the past, but for a brief moment visible here, again.