With the end of 2020 nigh, an unconventional holiday season is fast approaching. Our staff rounded up some of our favorites—books, but not just books—that may make a thoughtful gift for someone on your list.

In addition to book recommendations, I’ve broadened my suggestions to things life-related. I write this having just heard on the radio that New York City health care workers are receiving the first of the COVID-19 vaccines. The sense of relief is incredible. However, the pandemic is far from over and they are people suffering everywhere.

So, the suggestion to shop local has never been more important. If your town or city has a local bookstore, I urge you to order any of the following books: Ayad Ahktar’s Homeland Elegies; Martin Amis’s Inside Story; Teddy Wayne’s The Apartment; or Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. (Or even better, give yourself a gift and preorder several books.) Such purchases might just keep that beloved bookstore afloat between now and our nation’s recovery from this disease.

Finally, for the cook in your home—and if you’re like me, you’ve been cooking more than ever during this pandemic—I urge you to gift a subscription to the New York Times Cooking. It costs only $1.25 per week, and its recipes have been a source of joy, comfort, and education for me during these strange days of lockdown. This past week I made Roasted Broccoli with Almonds and Cardamon, and it was fabulous. Tonight, I’m trying the caramelized shallot pasta from the Top Recipes of 2020. A tip: Read the comments section before proceeding with any recipe. Invariably, people who’ve cooked the dish have learned something in the process and made improvements. Or having had to improvise, swapped out one ingredient for another.

—Adam Ross, Editor

This year I have grown to appreciate coffee-table books. After long hours Zooming and reading on the screen, I have no desire to subject my eyes to more screen time streaming shows or movies. Instead, I have enjoyed leisurely flipping through my little collection of coffee table books.

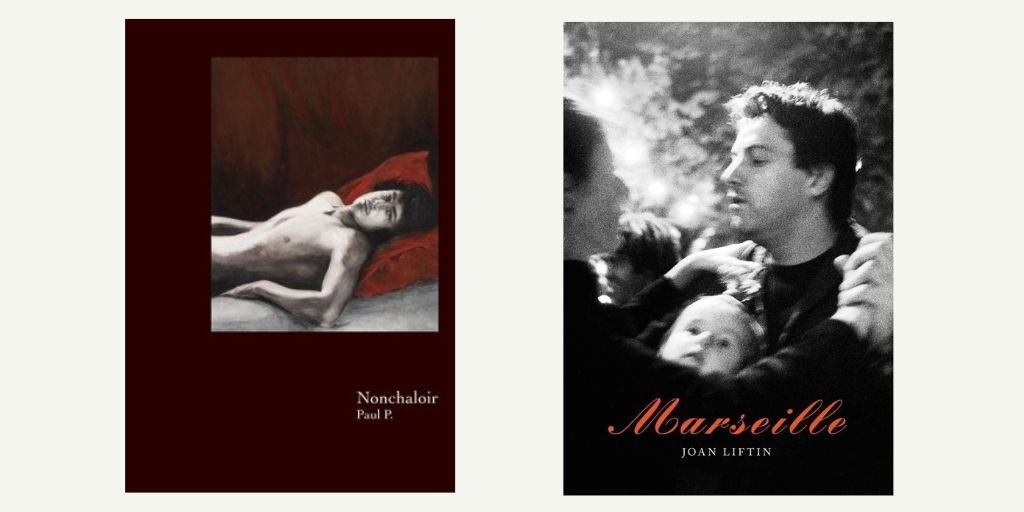

There is Nonchaloir by the elusive (even reclusive) Paul P. The book is the artist’s first monograph; it features P.’s portraits and paintings of young men taken from pre-AIDS gay magazines. The figures—faces and bodies of young men—are almost luminous; the color palettes that reveal their bodies are lucid, set against deep and warm rich tones—like eggshell or ecru colored silk against rich mahogany; you cannot help but look at these figures languidly reposed, leaning or sensuously stretching, and standing with their bodies curved and shoulders rounded. Sometimes they look back, their gaze uncannily present, unapologetic; sometimes they look up, down, and beyond the frame, lost in thought or enraptured by something unseen. It’s the haunting work of an aesthete who is looking closely—lovingly? achingly?—through an archive of a time right before a devastating epidemic.

And, too, there is Joan Liftin’s Marseille, a collection of the author’s photos from her ambulatory look of the French port city. These photos are a mix of many kinds of people: I mean of varying ages and races and professions against many kinds of backdrops. Street performers in an impossible tower rise high against a docking area; a faintly smiling couple look at each other, while their reflection in the mirror behind them, by a trick of angles and perspective, shows them kissing; a Muslim woman descends a Metro escalator, and her hijab radiantly reflects sunlight from some portal high above the photo’s frame. I believe Liftin when she describes France as “my other country” and of Marseilles’s inhabitants, “There they were, all my people. . . . This was more like it.” The photos reveal the kind of seeing of someone who belongs; they emanate the pleasing and satisfying freedom of being right at home.

—Hellen Wainaina, Assistant Editor

Oddly enough, one of my favorite Christmas movies has little to do with Christmas. Whit Stillman’s 1990 sleeper hit Metropolitan centers around the lives of ten debutantes as they navigate “the social season” over the course of their winter break. Although the film—an ode to Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park—parodies the elitist group, the “Urban Haute Bourgeoisie” (affectionately pronounced “UHB”), it evokes a charm and nostalgia for a New York Christmas.

Along the same vein, Kristen Richardson’s nonfiction work, The Season: A Social History of The Debutante, traces the social season from its flourishing in Regency England to the “downward social mobility” experienced in the 1980s to today. English literature’s most famous socialites—Edith Wharton and Nancy Mitford—even make an appearance during Gilded Age New York and prewar London society circles, respectively. Although Richardson, like Stillman, is the first to admit to the sometimes-absurd nature surrounding debutantes, she renders these women claiming their agency:

These young women who were presented to monarchs, who were betrothed to waning aristocrats, or whose fathers scrounged for money so they could walk across a stage and curtsy to a small-town mayor or rodeo clown, were united by an irresolvable dilemma—the only respectable career for women was marriage, and the best marriages were made by debutantes.

The Season documents a social practice rooted in the political and (misogynistic) social mechanisms of Western culture. It transports the reader from Old New York to the glittering age of café society—with far too many scandals in between, and unflinchingly looks at Antebellum South to the debutantes of the African American elite. Along with Metropolitan, these two are the perfect gift for a Janeite with a modern twist.

—Jennie Vite, Assistant Editor

This holiday season, give the gift of vicious awareness with Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy. This trio—Outline, Transit, and Kudos—sheds ten-kilowatt clarity on the human condition, brings an unrelenting exactness in its perspective. Cusk writes the stale breath between human interaction as well as the complexities of our personal dramas and desires, all while commenting on the way we invent and express our own narratives to others. Our narrator, Faye, is detached from her own life—each event or interaction spumes with her desperation to be inspired by or connected to something. As a result, she is completely vigilant about how she traverses her physical and social environments; much of the series is Faye relating the long-winded narratives (for paragraphs these people talk, uninterrupted) of each person with whom she interacts. This reporting reveals in our narrator a deeply relatable personal loneliness, and in others, a troubling, if necessary, vision of how much of our life we have made up and then convinced ourselves of.

Reading the trilogy was the extremely personal slap in the face I needed; after six months of solipsistic self-indulgence, Cusk brought me back into the real world where I have to acknowledge my pre-COVID concerns of personal narrative, relationships, and ennui; and she brought me out of my pandemic-invented sci-fi anxieties (last night I really did catch myself in monologue about alien invasion). These books remind me how much we learn from listening and watching; how essential attention and interaction are to the development of ourselves and our thinking. The Outline trilogy is a perfectly written series, both investigative and sentimental. It’s a necessary gift for yourself or your similarly disillusioned loved one. So go on, get the box set, light a fire, make a hot chocolate or head straight for the Schnapps. It’s been a long year.

—Julia Harrison, Editorial Assistant

I’ll admit to some editorial imposter syndrome when I belatedly meet our writers for the first time as we’re assembling an issue—Shouldn’t I know you a little better, I think as I select Track Changes, before I start moving your furniture around? But this wrong-way introduction to their work has a side benefit: it generates a self-selected reading list that’s perfect for short December days.

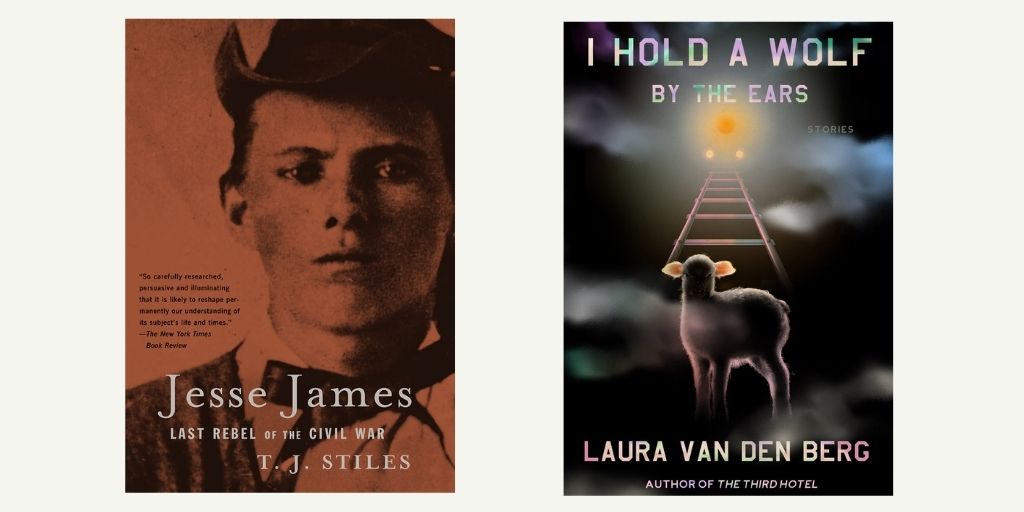

My evening read these days is T. J. Stiles’s revelatory Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War, which upends the myth of this homegrown terrorist in ways both exacting and painterly: How could I not love a book whose first sentence is “In the blind man’s memory, the river ran west”? Early next year, we’ll publish a craft essay by Laura van den Berg on boxing and writing. I’m in awe of the essay and equally taken by the kinetic stories in her latest collection, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears. My favorites so far are “Slumberland” and “My Second Wife,” and I’ve caught myself saying, Pray that we get the duplex just because it feels like the kind of sideways hopefulness one needs in order to choke down the dregs of 2020. Lastly, Alexander Chee’s revitalized blog is a must-read. Recent entries on MFA culture and writers block were exactly what I needed as I watched the wheels of my next book futilely spin in the mud that is the last half of the year. And I can’t stop thinking about his “Black Jeans” post from mid-November, which found me at exactly the right time:

Putting on these jeans was never meant to be a charm against all of that. It just means the first decision of the day has already been made and I can feel my way onto the path of another day. I can stand up and keep going, and these days that is a lot.

Here’s to keeping going—for the next few weeks and whatever’s after that.

—Eric Smith, Managing Editor & Poetry Editor

You can order many of these titles through your local independent bookstore or by shopping through Bookshop.org, which supports local bookstores with every purchase. Of course, we highly recommend giving a gift subscription to the Sewanee Review, the gift that keeps on giving (four times a year!). Be well and safe, and happy holidays!