Every year, we close the summer with our Labor Day staff picks. Though this summer never officially began, our staff has suggested some books to help keep the time over this long weekend, and beyond.

I used to be the most myopic reader, marching through every book in an author’s corpus, first to last. Now I’m always reading several books at once, and across genres. In poetry, I’m deep down a Camille Dungy wormhole, having devoured Smith Blue, Suck on the Marrow—maybe I haven’t changed that much—and most recently Trophic Cascade, which treats the subjects of race and our dying planet, and whose highlights, for me, are her series of “Frequently Asked Questions,” which are all about her new motherhood. A few of my favorite lines:

Is she talking yet?

She curses like a scholar.

She says, “MMMMMMM ffffffffffffffffff thhhhthththth”

Which roughly translates to, “May your fate by like that of Thebes.”

I also recommend Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, which is her illuminating analysis, from a writer’s perspective, of how certain white writers—Cather, Poe, Twain, and Hemingway—have tried to mediate and manage Blackness in their characterizations and how their literary structures often buckle under the stress of their depersonalizations of them. This is not an issue in Luster, the highly touted debut novel by Raven Leilani, which deserves all the praise it has received, and was for me one of the funniest and most acerbic looks at everything: from the impossibility of making it in the gig economy to life in present-day publishing, to the impossibility of being the third party in an open marriage. “‘I’m an open book,’ I say, thinking of all the men who have found it illegible.” Like that, from beginning to end.

—Adam Ross, Editor

In these strange times, when it seems everything is happening, nothing is certain, and I have a permanent migraine, the last thing I want to do for pleasure is scroll through hard-hitting no-nonsense nonfiction or the New York Times’ morning briefing or, God forbid, Twitter. No, my desire is to read something absurd, unserious, or at least seriously funny. Karen Russell’s Orange World delivers such relief in eight short stories that are playful, wild, and weird. Russell’s confident imagination deftly lifts you into the bizarre—she is sure of herself, her strange worlds, her dancing corpses, her tornado ranchers and stray dogs. With such a competent guide, her occult so understated, I found myself more invested in than disturbed by stories of a new mother nursing the devil himself; a prepubescent kid grappling with the 1,985-year age gap between himself and his bog-lady beloved; or a woman possessed by the spirit of a Joshua tree that strongly encourages her to kill her boyfriend. All to say: Orange World is an extra-strength ibuprofen. And it will keep you in your seat and off the news, if only for the long weekend.

—Julia Harrison, Editorial Assistant

The most ubiquitous photograph of Fannie Lou Hamer—organizer and voting and equal rights activist from the Mississippi Delta—was taken during her testimony at the Democratic National Convention in 1964. I have seen this photo many times; no doubt, if you’ve heard of Hamer, you’ve seen it too. Hamer is seated, leaning forward with her forearms on a table; a Sharpie-sized microphone is clipped to her chest: it sticks out against the pattern of her dress. She gazes forward with her mouth slightly open and her expression is . . . determined?

Hamer was at the DNC to give an account of “some of the brutality in the state of Mississippi” and voter suppression:

I stepped off of the bus to see what was happening and somebody screamed from the car . . . “Get that one there.”

. . . .

I was carried out of that cell into another cell where they had two Negro prisoners . . . by orders from the state highway patrolman

. . . .

I was beat by the first Negro until he was exhausted . . . After the first Negro had beat me until he was exhausted, the state highway patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack . . .

. . . .

All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens.

I’d never noticed until I started reading The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell it Like It Is (edited by Meagan Parker Brooks and Davis W. Houck) that in the photo her eyes are glossy, upwelling with tears. There is determination, and, if we elect to see it, an indictment. Listen:

I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.

. . . .

Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.

And, too, “if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America.”

A prescient statement indeed.

—Hellen Wainaina, Assistant Editor

I’ve been wary of picking up another novel with twin protagonists after I was let down by Cathleen Schine’s The Grammarians earlier this year (which had promised to be everything I adore in a book). Nevertheless, I decided to pick up Edmund White’s A Saint from Texas. And while I didn’t expect its particular everything, it proved to be everything I needed.

This coming-of-age novel follows two identical twins from an affluent Texas family: debutante and self-confessed Francophile Yvonne and pious Yvette. Narrated by Yvonne, who is just as witty as Elaine Dundy’s Sally Jay Gorce or Nancy Mitford’s Linda Radlett, the novel reconstructs the sisters’ lives from East Texas to Paris to the convents of Colombia. While Yvette makes a conscious vow to devote herself to others, Yvonne has a more practical ambition: marry into French aristocracy (unsurprisingly an easy ambition for an oil heiress).

Set in the 1950s, White doesn’t romanticize the world he creates. Instead, he highlights its racism, corruption, and inequality, and makes use of Yvonne’s cutting frankness: “[I decided to] pick myself up and become practical. I gave myself three assignments: (1) learn fluent French; (2) become a French aristocrat; (3) turn haughty. Tomorrow I would figure out how to do all three.” The novel’s social awareness is perhaps its greatest charm. While Yvette may hold the weight of the world on her shoulders, Yvonne is more attuned to her surroundings. She acknowledges the ludicrousness of the milieu she inhabits but, instead of accepting it, forms it in her image. That self-recognition is a comfort in these self-parodying days. Overall, it’s joyful and delicious—like being stuck in a technicolor dreamscape that glitches. It bears itself well, even under all the frills and jewels with which it’s trying to distract you.

—Jennie Vite, Assistant Editor

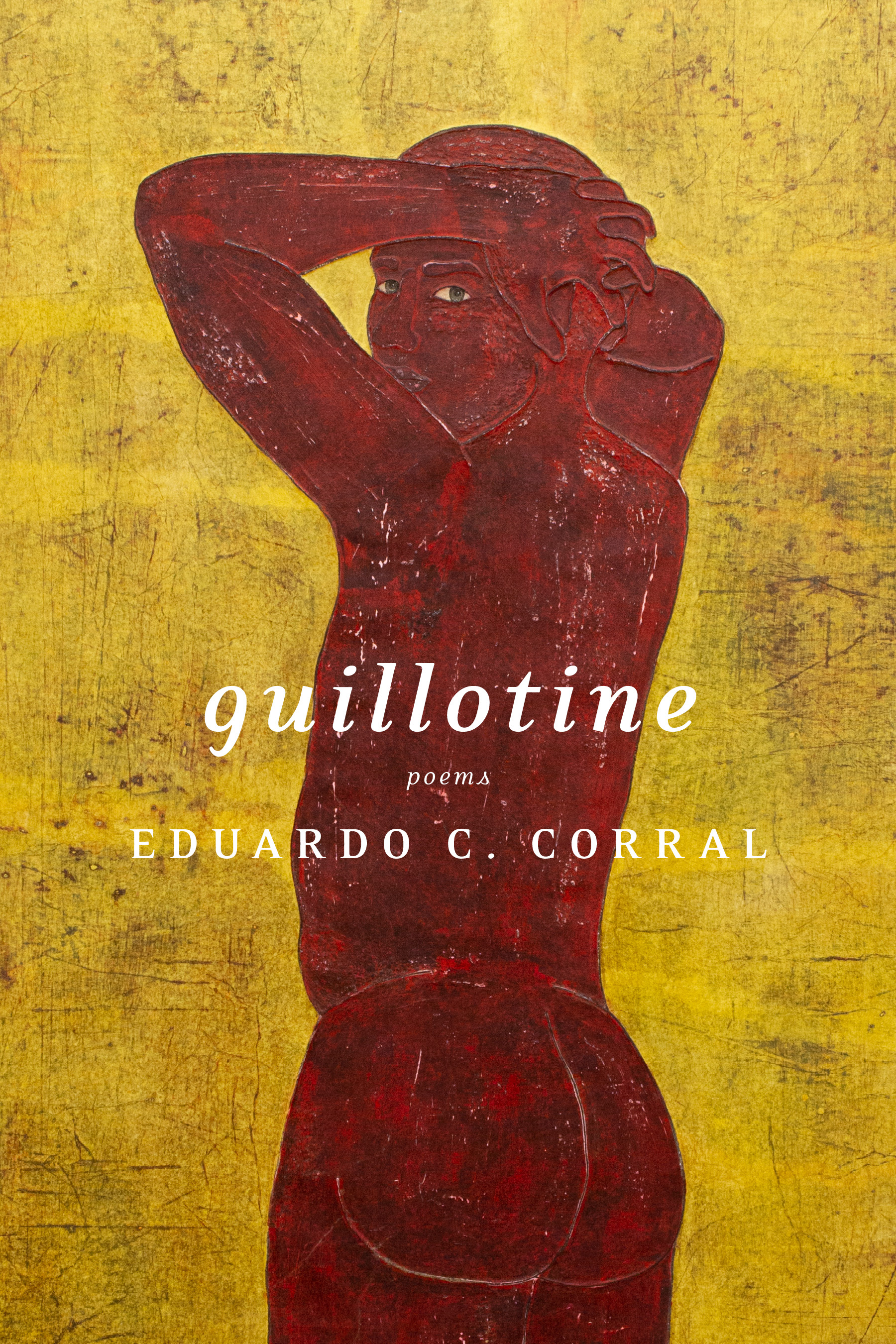

I’m making my way slowly through Eduardo C. Corral’s Guillotine, in part because I’ve been waiting so long for this book, but also because I find myself lingering over, transfixed by the work of one of my favorite poets.

Corral’s book (his second) is less written on the page than stapled to it: “an obsidian thorn pierces the moon’s ear” one speaker offers, while another describes the voice of a teenager’s reluctant and closeted lover as “six hummingbirds nailed to a wall.” One might also think of the loggerhead shrike, which pins its larder of beetles, lizards, and other small birds to the spiked knots of barbed wire fences. The collection is similarly adorned with what remains behind: in one poem, “tinder. / Paper. Shed snakeskin.” In another, “a kimono of pressed-together dust.” There are mirrors, snatches of song lyrics, and in “Border Patrol Agent,” a persona poem that inventories, among other horrors, “Legs / gnawed to the knees, barbed wire tight / around // the throat.”

This collection is one that also occupies and is interrupted by borders—between bodies and their desires, between nations and their promises—that are hastily demarcated and militantly patrolled. The punishment for those who transgress such borders—by being queer, by being brown, or by being both—is one of the collection’s central occupations, and illustrated to astonishing effect in the ekphrastic sequence of poems titled “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel.” In one section, the border is a broad channel splitting the page, the poem’s unpunctuated text contrapuntally anchored on either side while also flitting across that gulf of space, amplifying one of the poem’s earliest admissions: “everything // is plural in my throat.” In the section that follows, the border collapses, as do time and memory, and the poem, addressed to the speaker’s sister (her name a refrain), makes the crossing again and again, forcing us to traverse the many possibilities Corral places on the page:

Sister, we crawled

I’ll be hiding out through thorns,

in Raleigh, scrambled over

a few blocks barbed wire. Sister,

from our cousins, as he skinned

in a trailer the rabbit

How to read lines like these? Such a poem demands rereading, recasting, even re-embodying these impossible navigations. In “1707 San Joaquin Avenue,” a sequence which draws on news reports of drop houses in Arizona, the border collapses entirely in a visual poem comprised of the pentimenti of names of those who made (and remade) the crossing. It’s difficult to say what the poem is: the names are layered on one another, etched and ghosted, branching like a family tree and fading like rubbings from headstones. However it’s approached, the poem—and the collection as a whole—confront the reader with a stark reminder: the stories we tell are almost always written over someone else’s pain.

—Eric Smith, Managing Editor & Poetry Editor

We also recommend the Review’s Summer 2020 issue, furnished with humor and sorrow, winter in New York and summer in Rome, and more for these febrile times (read more about it in our editor’s note). These days are predictably long, but the Review is reliably new (since 1892). We hope you’ll subscribe.