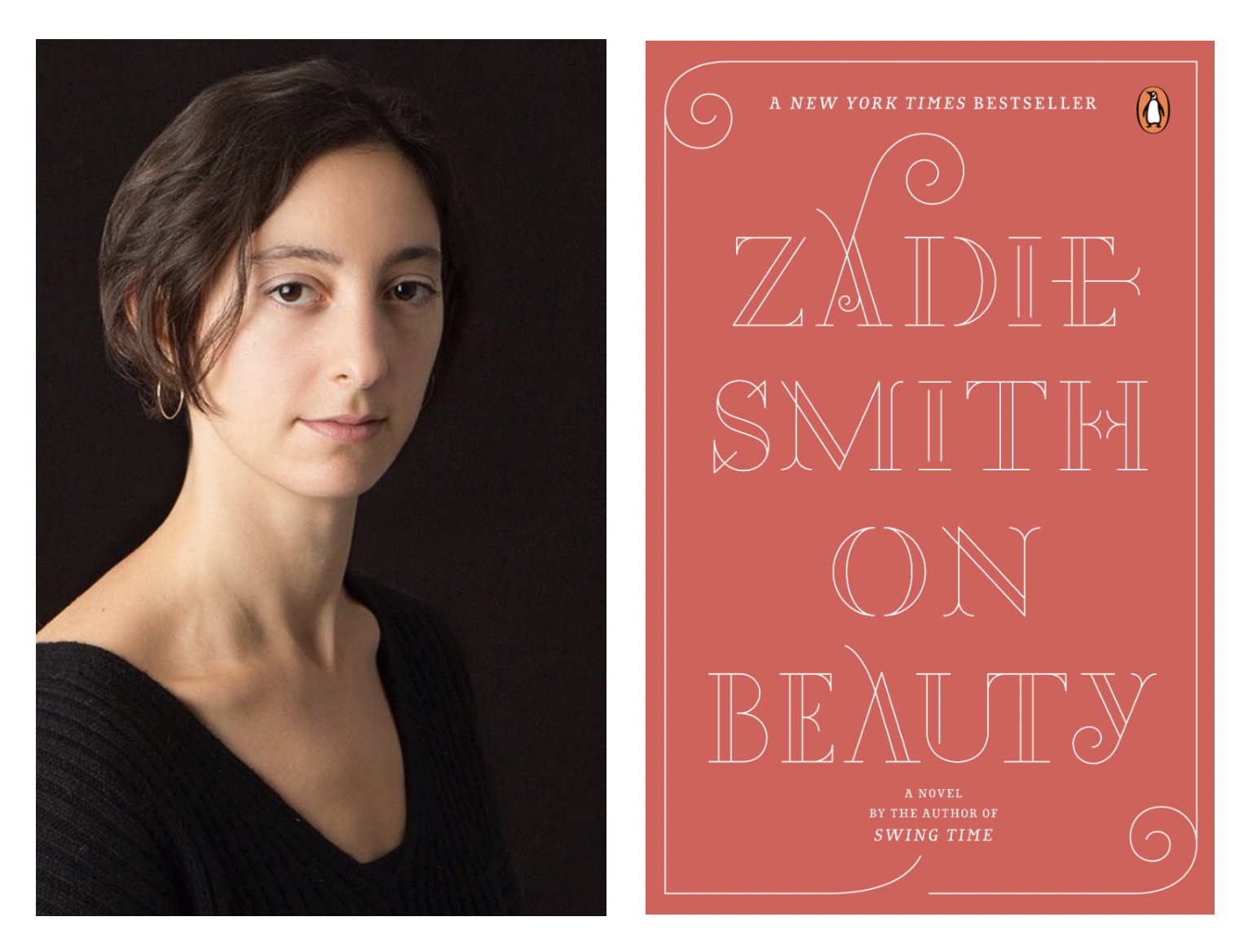

For our Marginalia web feature, we ask writers to introduce us to their favorite works of literature by way of a short piece of prose. This week, Lily Meyer—winner of our 2018 fiction contest for her story "On Being Human"—examines a scene from On Beauty by Zadie Smith.

Harry just wanted Howard to sit down, start again. There were four more hours of quality viewing lined up before bedtime—antique shows and property shows and travel shows and game shows—all of which he and his son might watch together in silent companionship, occasionally commenting on this presenter’s overbite, another’s small hands or sexual preference. And this would all be another way of saying: It’s good to see you. It’s been too long. We’re family. But Howard couldn’t do this when he was sixteen and he couldn’t do it now. He just did not believe, as his father did, that time is how you spend your love. And so, to avoid a conversation about an Australian soap actress, Howard moved into the kitchen to wash up his cup and a few other things in the sink. Ten minutes later he left.

–Zadie Smith, On Beauty

In On Beauty, Zadie Smith loosely retells or reinvents E. M. Forster’s Howards End, a novel best remembered for the dictum, “Only connect!” On Beauty, though, takes less interest in connection than in its failures, which Smith’s omniscient narrator describes with heart-stopping precision.

Here, Howard, a British academic living in Massachusetts, fails to connect with his aging father, who he speaks to infrequently and visits even less. Howard, Smith writes, “liked to keep his working-class roots where they flourished best: in his imagination.” Perhaps that explains why this visit goes, as Harry might say, tits-up.

Smith begins Howard’s departure from Harry’s perspective, all bewildered sorrow and irrelevant detail—“this presenter’s overbite, another’s small hands.” But Harry understands that those details aren’t relevant, and his understanding becomes the fulcrum on which the paragraph turns. Harry wishes he could say, “It’s good to see you. It’s been too long,” but he is no more capable of this expression than his son. That shared, unspoken sentiment swings the narration from Harry’s mind into Howard’s, where detail is replaced by disbelief. Suddenly, the sentences shift from bewildered to brisk. Howard doesn’t believe in Harry’s time-spending love, and so the scene has to end. No lingering. Got to go.

So often, love fractures in this way. What long relationship is not filled with the frays and cracks of the wrong departure, the wrong silence, the wrong way of showing love? An omniscient narrator can explain why people fail to connect. We readers have to figure out our failures on our own.