With the season of giving (last-minute and otherwise) approaching, our staff rounded up some favorite books that may make a thoughtful gift for someone on your list.

I resist gifting poetry at the holidays (it’s usually received with as much joy as a reminder to eat your vegetables), but I’m tempted to pile a dozen copies of Oblivion Banjo: the Poetry of Charles Wright beneath the tree this year. At its best, Wright’s work is meditative, transcendent, and deeply generous—both to the natural world that is often its subject and to the reader who lives in it. I’ve loved his homespun gnomic symbolism for the better part of fifteen years, and to have it all under a single cover is a pleasure I didn’t know how much I was looking forward to.

Three cheers, too, for FSG and Crisis, who have designed a book that is as generous as its author. Too often, a poet’s work in a selected or collected is cramped to the point of unreadability or freighted with the shelf-warping tonnage of the poet’s genius-slash-prolificacy. But here, the rewards of good design are immediately felt, allowing us the pleasures of sustained reading, or of a more opportunistic swanning, as I did this morning, into this passage from Littlefoot:

August, blue mother, is calling her children in

soundlessly

Out of the sun-dried thistles

And out of the morning’s dewlessness.

All of the little ones,

the hard-backed and flimsy-winged,

The many-legged and short-of-breath,

She calls them all, and they come.

Listen, this time I think she’s calling your name as well.

The morning’s dewlessness! What better gift to unwrap this year than this.

—Eric Smith, Managing Editor

I'm recommending Lorrie Moore’s Like Life. The stories in this collection are as heartfelt and whimsical as they are grim and bleak. The worlds that these characters inhabit are a “land of perversities,” as Moore puts it, where characters encounter their doppelgängers, loved ones are resurrected, and apartments disintegrate, while living out extremely mundane realities: like in “Joy” where plot entails taking a cat off at the vet or in “Starving Again” where a hapless romantic discovers self-help books post-divorce. The first story, “Two Boys,” appears to be a comedy of manners as it follows our protagonist Mary’s relationships with a married politician and a devoted, unnamed second man—affectionately labeled Number One and Number Two. However, we realize that these men are incidental, and that Mary’s apartment becomes more realized, more human than any of the characters:

She lived in a small room above a meat company—Alexander Hamilton Pork—and in front, daily, they wheeled in the pale, fatty carcasses, hooked and naked, uncut, unhooved. Every day she attempted not to step in the blood that ran off the sidewalk and collected in the gutter, dark and alive.

As much as the characters attempt to conceal the increasing filth around them—Moore won’t allow them to ignore it. My favorite story, which gives the collection its title, follows a couple living in extreme poverty. Riddled with anxiety, Mamie and Rudy endeavor to rid themselves of their soiled home—and each other. It’s a painful portrait of a marriage, but even more so it’s a recognition of one’s realities. Moore doesn’t allow for self-delusion, instead calls for poignant honesty: “you could get to calling everything false and willowy and never know anymore what was true and from the heart.”

—Jennie Vite, Editorial Assistant

Communion: The Female Search for Love was a gift to me from a wise, loving, and long-time mentor and friend. It took me a year to get to it, but I wish I hadn’t waited so long. It’s about love—that dangerously elusive, hard to define word—by the visionary thinker and critic bell hooks. hooks proposes an intrapersonal transformation to propel a cultural revolution: “Feminist silence about love reflects a collective sorrow about our powerlessness to free all men from the hold patriarchy has on their minds and hearts.” She examines the feminist reluctance to speak on love, to publicly claim the longing for it, and the profound disappointment in not finding it, as a result of patriarchal ideas of love as the domain of the meek and weak. Still relevant in 2019 are her concerns that many of us remain underdeveloped intellectually and emotionally when it comes to love: for men who remain “emotionally crippled adolescents,” and a generation of women “encouraged to remain in a state of arrested development, to be emotionally underdeveloped, adolescent girls.”

This is not a surface level look at love, not simply love languages or modification of behavior, but a deep interrogation of how American culture has taught us what love is, how to love, and who to love. Read it once, gift it twice: as I write, two copies, wrapped and addressed, are in the mail, on their way to their recipients.

—Hellen Wainaina, Assistant Editor

A book of correspondence between two of my favorite American writers, Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick, was released this week. It’s called The Dolphin Letters: 1970-1979, and collects letters that inform one of my favorite books, Lowell’s The Dolphin, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1974. It is, admittedly, a difficult book to like, as so much of its material is lifted from letters written between Hardwick and Lowell at the time of their divorce, prompting Elizabeth Bishop’s famous rebuttal: “Art just isn’t worth that much.”

In that spirit, I’ve chosen to recommend Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights (1979), which is something like a novel-as-diary-as-epistle—at turns difficult (as in smarting and intense) and intimate. Its elision of narrator and narrative provokes one of the great questions/theses/mission statements in literature: “Can it be that I am the subject?” It can be, but never completely. There’s so much fruitful contact between writer, reader, and the written, so much said that could have been otherwise, so many gaps worth falling into with and beside Hardwick’s narrator/nemesis, who deploys peerless sentences like these:

He was terrible to look at. Very short, and if not fat, with too many muscles and bulges. Bernie was put together like a pumpkin or two pumpkins, one placed on top of the other. The top was his merry, jack-o’-lantern face with its broken teeth.

It’s funny stuff, and so often scary (the best jokes always have a little bit of both).

—Spencer Hupp, Assistant Editor

I've been reading so many terrific things it’s hard to know which book to suggest. John Lahr’s biography of Tennessee Williams, Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, is masterfully told, reveling in the joys of Williams’s early, stratospheric successes with The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire while always keeping an eye on the playwright’s destructive nature. Lahr’s keen psychological insight is matched by his brilliant critical assessment of Williams’s work, play to play, which means that it’s a pleasure on all levels, literary and otherwise, and confirms that Williams remains one of our most important and enduringly interesting twentieth-century artists.

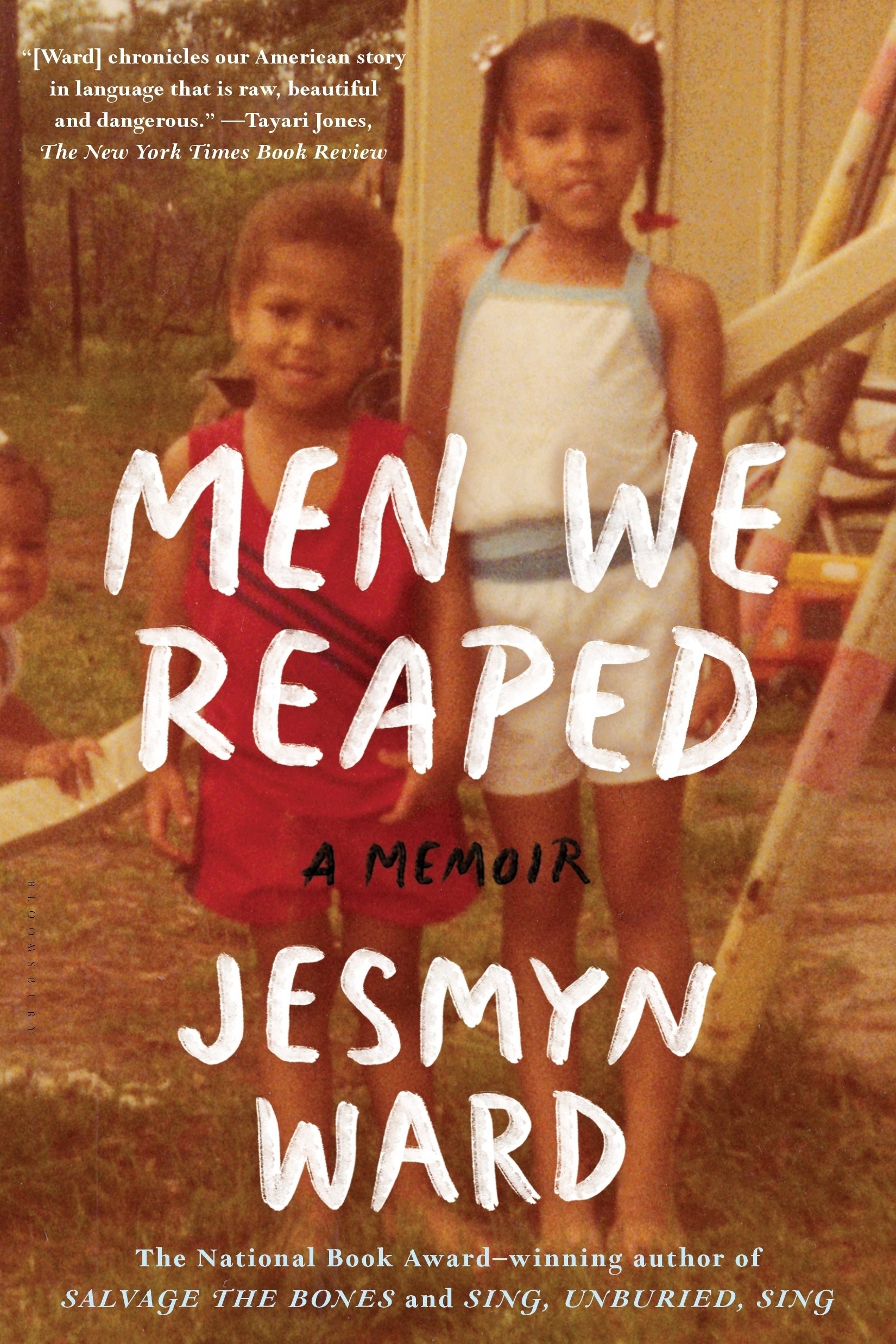

I’m also loving the early goings of Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror. Tolentino is a writer who seems able to speak directly to the willful delusions we participate in as we live more and more of our lives online: “Even as we became increasingly sad and ugly on the internet,” she writes, “the mirage of the better online self continued to glimmer.” True that. However, the book that rocked me to my core, and that I’d stuff any stocking with, is Jesmyn Ward’s memoir Men We Reaped. On one level it tells the story of five men Ward lost to tragic deaths between 2000-2004, including her brother, Joshua; on another level, it's a portrait of a black community under systemic attack and the struggles these individuals and families endure as they try to survive life in Delisle, Mississippi. Ward speaks to racism and its human costs so that we, who partake of comfort and joy, remember that all around us there are those who are in need, those who are disadvantaged, those who are succumbing, and that this country has a long way go when it comes to racial justice and equal opportunity.

—Adam Ross, Editor

Of course, we highly recommend giving a gift subscription to the Sewanee Review, the gift that keeps on giving (four times a year!). Subscribe or purchase your gift today.