Next Thursday, March 19, spring officially arrives. This week our staff came together to share some good reads to tide us over for these last, ailing days of winter.

I’m toggling between three books right now and have been trying to recall when this happened to me. When I shifted, that is, from my more youthful, myopic reading habits—thumbing through one author’s work, chronologically, a book at a time—to this tapas approach, sampling what’s new along with old favorites. I’ve been a bit stymied by Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends. I’m deeply impressed by her fluency, the ease with which she renders place, conveys a skin-to-bones knowledge of this quartet of characters—Frances, Bobbi, Nick, and Melissa—as their lives intermingle, and they vampirically exchange innocence for experience in a pair of sexual and emotional affairs. She writes movingly of the toll of alcoholism and economic uncertainty on a country and its people, although I confess the tale itself doesn’t often bring news, as if Maria Callas were singing a Britney Spears song and exposing its thinness, beautifully. Sewanee Review contributor Cally Fiedorek will be reviewing National Book Award winner Phil Klay’s highly anticipated first novel The Missionaries in our Fall issue, so I’ve been re-reading his 2014 story collection Redeployment. It’s a mordantly funny look at the toll of the Iraq war on its soldiers and families and speaks even more clearly now to the numbing, purgatorial fact of our Middle East military adventures. It’s also disturbingly prescient: like its series of narrators, we never really left, bugged out, finished our tours there, and have paid the most terrible price of blood, treasure, and lost time. Finally, I’ve just started the Everyman’s Library edition of Lorrie Moore’s Collected Stories, which has a lovely introduction by SR contributor Lauren Groff and is a tonic to the imagination. It’s important to keep a favorite genius by your bedside table to not only remind you why you love literature but what being in the presence of brilliance feels like. “Her mother,” begins “Agnes of Iowa,” “had given her the name Agnes, believing that a good-looking woman was even more striking when her name was a homely one.” Before the paragraph’s concluded, Agnes, we learn “turned out not to be attractive at all.” And there you have it, an entire metaphysics along with a mother’s hubris in the tale’s first three sentences. Make plans and God laughs. That’s a tapas dish best served cold.

—Adam Ross, Editor

More welcome than the discovery of a single good book are the strange correspondences that magpie-ing around in a few of them at a time introduces. I recently finished Tom King and Mitch Gerads’s Mister Miracle, and this week, Eric Tran’s new book of poems The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer arrived. Because of it, I’m meeting for the first time a poet who seems to love, as much as I do, the sacramental surety of a good nine-panel grid (as well as the all-time greatest run of the X-Men, Grant Morrison’s). Tran also deftly closes the distance between comics and poetry by exhibiting in his work the economies of image, space, and kinetic movement that both of these arts share. I’ve been savoring these lines from “Lectio Divina: Big Barda and Mister Miracle”:

In the dark, my love, I could be

your window of flame—but

to save the candle, you have to

snuff it out.

Such truths offered about the conundrum of illumination brings me to another recent favorite that I’m again rereading, Andrea Cohen’s Nightshade. Here, in full, is that collection’s “Night”:

Someone was talking

quietly of lanterns—

but loud enough

to light my way.

I’ve long adored Cohen’s poems for their compression, despite which she never sacrifices heart or a subtle, wounding humor (her “Worry,” another favorite, is comprised of these two lines: “Will there be / enough beads?”). What a gift, a new book by a favorite poet. What a gift that it’s her best yet.

Lastly: my wife and I are expecting our first child in a couple of months, so I’ve been revisiting Chris Bachelder’s essential primer on dadhood, Abbott Awaits. I’ll never tire of this sentence: “All Abbott wants right now—the only thing—is to be knocked unconscious by the long wooden handle of a lawn tool.” Instructions for living, indeed.

—Eric Smith, Managing Editor

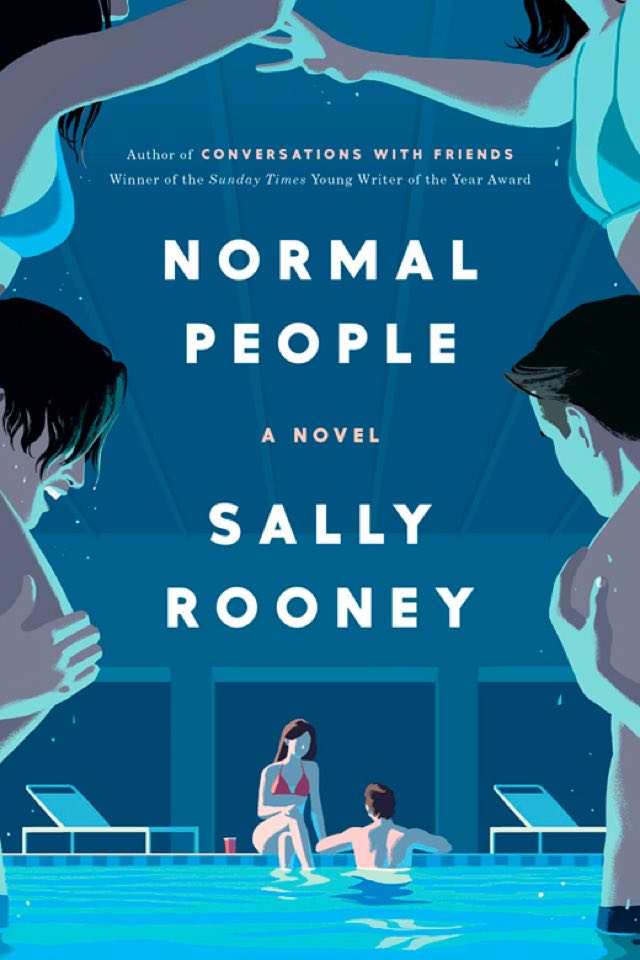

I am recommending Sally Rooney’s Normal People—now in development for a Hulu miniseries—which follows the it’s-complicated relationship between Connell and Marianne that begins in a school in a small town in the west of Ireland and extends through their undergraduate years at Trinity College. In Normal People, what is novel is the characters’ self-curation. Its seductive, lose-yourself-in-the-book charm has to do with the tension within both Marianne’s and Connell’s invested efforts to project an outward self in spite of the debilitatingly insecure and anxious internal self.

Rooney, I think, is of the genus of writers who suggest that not only are we—millennials—all swimming in narrative but we have also finessed a (capitalistic) system to value the aesthetics of the “pool” via character development; turning day-to-day living into a lifestyle by curating I as character (also known as an influencer).

About Marianne, Rooney writes, “Almost no paths seem definitively closed to her, not even the path of marrying an oligarch”; she “often feels there’s no limit to what her brain can do, it can synthesize everything she puts into it. . . . Really she has everything going for her,” except, “she has no idea what she’s going to do with her life.” Here, the belief in an ability to be as you would imagine is stymied by one’s own brazen freedom. A low-stress tolerance for metamorphosis: what is that if not a millennial paradox.

—Hellen Wainaina, Assistant Editor

I’ve lived with the (latish) news of Luis Muñoz’s poetry for weeks and must now deliver my full-throated commitment to his work; that it constitutes, in Curtis Bauer’s studied and electric translation, one of the finest and fullest bodies of writing in our adolescent century. Muñoz is a Spanish poet who splits his time living in Madrid and Iowa. That transit, among others, is one of several “distances” which this book, From Behind What Landscape: New and Selected Poems, mines fruitfully. From “Blackfriars”:

Only if you are far away is it possible

to love the distance

and transform the fog

into a sad passage

and perceive if you are alone

or part of the life of others

These poems are both in and of spaces, and attempt, therefore, to map the self’s proximity to other selves, other souls (which is, of course, the project of all great poetry). I relish his lines for their tenderness and accuracy, and for their war with time: :

September is no more real than a memory,

but names we gave up for lost

recover their clarity, the air they attract

and the dream in which summers make their stand.

This contest ends, as always, with a careful kind of resignation; life and time happen at such ordinary, graceful pace in these poems, confirming one’s notion of poetry as a timing device. Here’s the ending of “This is Not an Experience”: “His name was David, or so he told me, / and he was only interested in what was possible, / and helped his mother in a seamstress shop.” These aren’t mere moments or experiences, but a life in three lines; they exist in themselves and for themselves. Such is Muñoz and his cautious, confirmed humanity, which shows what people and poems can be and, eventually, are.

—Spencer Hupp, Assistant Editor

Around the same time I was absorbed by Deborah Levy’s part memoir, part manifesto The Cost of Living, I revisited one of my favorite Jane Austen novels, Persuasion: “I hate to hear you talk about all women as if they were fine ladies instead of rational creatures. None of us want to be in calm waters all our lives.” Like Austen, Levy doesn’t want you to remain in calm waters. In fact, she’s the one who throws you overboard:

Everything was calm . . . And then when I surfaced twenty years later, I discovered there was a storm . . . I wasn’t sure if I’d make it back to the boat and then I realized I didn’t want to make it back to the boat. Chaos is supposed to be what we fear most but I have come to believe it might be what we most want.

The boat becomes a metaphor for Levy’s sinking marriage and the “tempest” the place where all of her greatest anxieties reside. Like the rough waters that beckon us back to the sea, we as readers are repeatedly drawn back to examine Levy’s wreckage. But she doesn’t use her suffering to make voyeurs of us, instead she sets out to do something altogether extraordinary: taking all of the grief, discomfort, and trauma of a life and transforming it into power:

She said that she gave herself permission to speak ‘in a sense totally alien to women’. I know what she means. It is so hard to claim our desires and so much more relaxing to mock them.

The Cost of Living is an unfettered, honest look into Levy’s life and how she refuses to reduce herself in the face of turmoil: “Life falls apart. We try to get a grip and hold it together. And then we realize we don’t want to hold it together.”

—Jennie Vite, Editorial Assistant

Remember that you can find a local bookstore—many of which are currently offering discounts on books and shipping—using IndieBound’s Indie Bookstore Finder, and you can also support local bookstores by shopping through Bookshop.org. We also highly recommend the Review’s latest issue, Winter 2020, whose pieces, as Ross writes in his editor’s note, “like an unexpected snowfall . . . an overnight dusting . . . surprised us and lifted our spirits.” We hope you’ll subscribe or give a gift subscription.