As we wade into summer, our staff came together to share some reads to accompany you wherever you are, whether you’re staying put or gingerly taking advantage of relaxed travel restrictions.

Isabel Wilkerson’s nonfiction Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents has justifiably received massive praise since its publication in August of last year. The book’s focus is the “unseen phenomenon” of caste in American culture, and how so many of its foremost ills, especially racism, are simply offshoots of this system or enabling engines of it. “Caste and race,” Wilkerson writes,

are neither synonymous nor mutually exclusive. They can and do coexist in the same culture and serve to reinforce each other. Race, in the United States, is the visible agent of the unseen force of caste. Caste is the bones, race the skin.

It is one of those books that, as you read it, you feel your entire conception of the American experiment, and the country’s history, being recalibrated. It is also a book that brings all sort of news: it recounts, in unsparing detail, the violence that attended the maintenance of our country’s slave-based economy and the traumas that attended the Jim Crow South in such a way that the shame one feels affirms all of our current social justice conversations; it explains, in granular detail, the Indian caste system, and its stultifying stratifications. It also instructs in ways that are utterly surprising: that, for instance, the architects of the Final Solution, when creating its own caste system to systematically exterminate the Jews during the Wannsee Conference, could not bring themselves to embrace the same level of cruelty regarding America’s treatment of its own people, at least at the level of jurisprudence: “The men who gathered for that meeting,” Wilkerson writes, “did not agree on how much to draw from American jurisprudence. The moderates at the table, among them the chair himself, Franz Gürtner, argued for less onerous methods than the Americans were using.” I cannot recommend the book highly enough.

It’s also hard to know what to say after reading Lisa Taddeo’s Animal, her follow-up to her world-beating nonfiction book, Three Women. It tells the story of Joan, a woman who, after the suicide of her married lover, barrels from New York to California on a mission of what is either revenge or redemption. The body count along the way is high; the events are garish and ghoulish. It doesn’t seem to matter, since Taddeo lights Joan’s journey to hell with all sorts of bright truths. In fact, Animal lit up so many of my pleasure centers, I just enjoyed it so much, I still find myself a bit flummoxed responding to it. It is riveting, important, and relentless. It is propulsive and preposterous, like all lives lived at the edge. It is also a joy to witness Taddeo enter the literary landscape as a novelist, full-throated and in full flight. (If the stories the Sewanee Review has published by Taddeo are any indication, stay tuned to see her enjoy the same thumping success in that genre.) My writing teacher, Stanley Elkin, used to say that the greatest revenge a writer can enjoy is the revenge of style. You read a sentence only that writer could have written and that recognition is the mark of her triumphant art. I hereby offer a pair (from countless examples) of the Taddeo paragraph, which is now officially inimitable:

Old men are so sure of everything. He was forking broccoli into his mouth. I tried to determine whether he had dentures. Or he could have had caps. He came from a wealthy family. Now he was worried about air conditioners but that is how all old people end. More surely than we fly toward death, we go to parsimony.

Or:

I wasn’t able to relax that night, but there nothing better than fucking a beautiful man who is also kind and elusive. I faked an orgasm forty minutes in. I liked that he brought his mouth between my legs after we’d already started fucking. I liked the messiness. I looked up through the skylight at the wolf-gray stars and cried out like I was calling up to someone in the galaxy. I looked down to see the proud look on his shining face. The dog, Kurt, lay near the door, his chin resting on his paws, watching sex the way dogs do, like they are confused as to why you’re making more of it than it is.

Expect this novel to be number one, then—and here I give nothing away—with a bullet.

—Adam Ross, Editor

Weeks after one copy was lost in the mail and its replacement long-delayed, I’m happy to report that Barbara Ras’s fourth collection, The Blues of Heaven, found me when I needed her poems more than I realized. I’m a longtime fan of her work (I’ve done my best to explain why elsewhere), and her latest doesn’t disappoint. You'll find Ras’s usual sunny, kaleidoscopic amalgamations of the world’s ordinary wonders; mantis shrimp, mares’ milk, Mister Potato Head, and Manu Ginóbili all make appearances (and that’s just the m’s). Her poems regularly threaten to brim their banks with enthusiastic enjambment, their lines shaped by a deceptive breathlessness, as is the case here, in this selection from “Tuesday”:

Upstairs, organ music is playing, Duruflé’s

“Prelude and Fugue on the Name of Alain,”

pipes full of loss and petals,

faith rises and falls, scarves in the wind,

while a man in the park leaves his wife for a woman

who has just given up a kidney for a stranger, and millions

of leaves and leaves and leaves fall in just half an hour.

Since her previous collection, The Last Skin, Ras has been working in increasingly shorter (for her, at least) forms. And while the poems of hers that I first loved most tended to chew through their margins and onto additional pages, I’m consistently in awe of this collection, of what she accomplishes with such measured reductions in poetic real estate, as she does in concluding lines of the poem “Waves”:

today I hear in every wave hitting the shore a door

slamming on my own selfish ache of what I would give to make

the ocean home again.

Under such restraint, the poems’ amplitudes—both in their music and their emotional range—has increased. What becomes clearer in reading them is that Ras is engaged in nothing less than what she describes in “Not a Jelly Bean” as “the archaeology of the eternal.” Somewhat paradoxically, these shorter poems seem more suited to such careful excavations. And it is in this collection—the poems at once tender and world-weary, weathered but endlessly hopeful—that we see Ras at her best.

—Eric Smith, Managing Editor & Poetry Editor

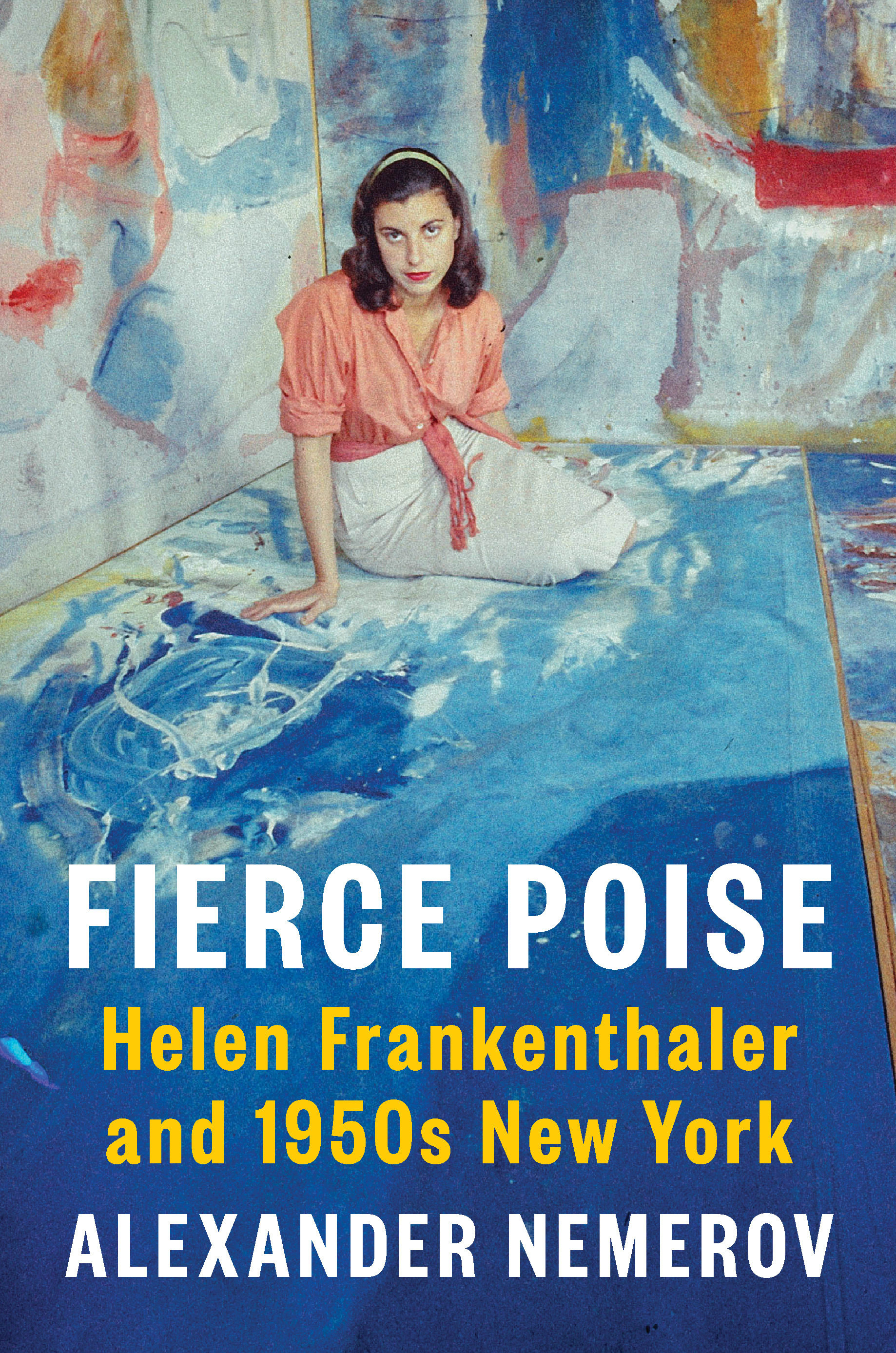

Given the recent revitalization of and fascination with the fine art market and art galleries—in part due to popular documentaries like Made You Look and This is a Robbery—I was excited to discover Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York by Alexander Nemerov, published earlier this year. I admit that Helen Frankenthaler is an artist whose name has only vaguely passed through my life: I remember viewing her works at the National Gallery of Art on a trip to DC; and her most coveted work, Mountains and Sea (1952), inevitably made its way into a lecture I attended on Western Art. But aside from an initial feeling of confusion and frustration on viewing her abstract works, I hadn’t given Frankenthaler much thought or reexamination. And she deserves so much more than that.

From the outset, Nemerov—whose father, the poet Howard Nemerov, taught at Bennington College while Frankenthaler was a student—makes his intentions clear: “True to Helen, this book takes on the formative decade in her life and early career in the form of days. . . . Each chapter centers on a specific date, starting in 1950 and ending in 1960.” This fluid reconstruction of Frankenthaler’s beginnings as an artist is a testament to her life’s work; work that is spontaneous and unexpected. The microcosmic scope allows Nemerov to distinguish some of the most fundamental moments that shaped Frankenthaler’s career: from attending an exhibition of Jackson Pollock’s work at the Betty Parsons Gallery; to a solo trip to Spain in 1953, where she encounters and becomes fascinated with the prehistoric cave art of Altamira.

Along with Nemerov’s precise narration, myriad letters and interviews from friends and colleagues help paint a complicated portrait of Frankenthaler. My favorite of these is of the friendship between Frankenthaler and Frank O’Hara, leading Nemerov to an evocation of one of Helen’s parties in 1966, shortly before O’Hara’s passing:

At a party likely at Helen’s in early 1966 O’Hara would scribble on the back of an envelope: “Dear Helen—I loved your party,” before crossing out the word “party,” the “d” in “loved,” and the “r” in “your” to leave the sentiment: “Dear Helen—I love you,” to which Helen responded on the same envelope: “& I love you because you’re my first syllabil [sic].”

In order to fully appreciate and understand Frankenthaler’s paintings—paintings that have been called “unfinished,” and a “celebration of mediocrity” by critics and spectators—one must examine and understand her life: her insecurities, her dreams and aspirations, and her personal reckonings, which are all laid bare in her paintings. Her work is not drawn from or even inspired by real life, rather her paintings are life.

It’s striking to read how her early ascent into the art world was coupled with her dismissal; a sentiment that I find very hard to shake because she was one of the first female artists to have the social and economic freedom usually reserved for her male counterparts of the time. But Nemerov’s biography doesn’t just give its readers insight into Frankenthaler as an artist; as importantly, he renders her with the sensitivity and grace of a young girl beginning to find her footing in the world.

— Jennie Vite, Assistant Editor

I’m recommending Red Island House by Andrea Lee. Lee’s novel follows Shay, a Black American woman from Oakland, California, who at the start of her professional academic career in Milan marries a wealthy Italian businessman, Senna. Prior to their marriage, Senna, like a “djinn out of Arabian Nights,” constructs the Red House, “a structure of fanciful grandiosity, a pastiche of tropical styles from around the world” in Madagascar. He presents it with pride to Shay—who has “a scant interest in the continent of Africa except as a near-mythical motherland”—the house becoming their summer vacation home away from Milan.

Swept up in the whirlwind of this unlikely romance, Shay is at once proud of the house’s beauty—its harmony with the surroundings (and, really, proud of her husband’s taste)—and put-off by an unnamable discomfiture:

Not its architecture, but its mere existence is an error in a way she can’t yet define, but which goes beyond being an emblem of wealth in a land of poverty. . . . Her new husband has raised a monument to an unseemly private fantasy. And now . . . she somehow shares the blame.

Nevertheless, Shay passively accepts becoming “the chatelaine” of this “neocolonial pleasure place.” From this point, the novel traces a gradual, if at times reluctant, awakening. Over the course of twenty years’ worth of vacations—which the novel details in loosely independent episodes—children are born and raised, friendships with the locals are formed, the house is transformed into a partial hotel, and the marriage disintegrates. In the midst of this, Shay discovers how she belongs. Out of the role of the chatelaine, an “almost a burlesque of that of the plantation ladies she [Shay] always scorned: mistress of a colonial-style household in an African nation, where a troop of Black servants labor for her comfort,” Shay forges a new understanding of herself and of the privilege which catapulted her into a reversal of the Atlantic triangular trade.

The real pleasure of reading Red Island House arises from moments when a character’s total confusion looms toward discovery. Lee’s prose, in its singular lucidity, sutures contradictory realities borne of complicated histories, perhaps offering something like “a modicum of principle, if not grace,” as Shay thinks, for how to define the self and live in such a way that our “leisure” is not “built on old crimes.”

—Hellen Wainaina, Assistant Editor

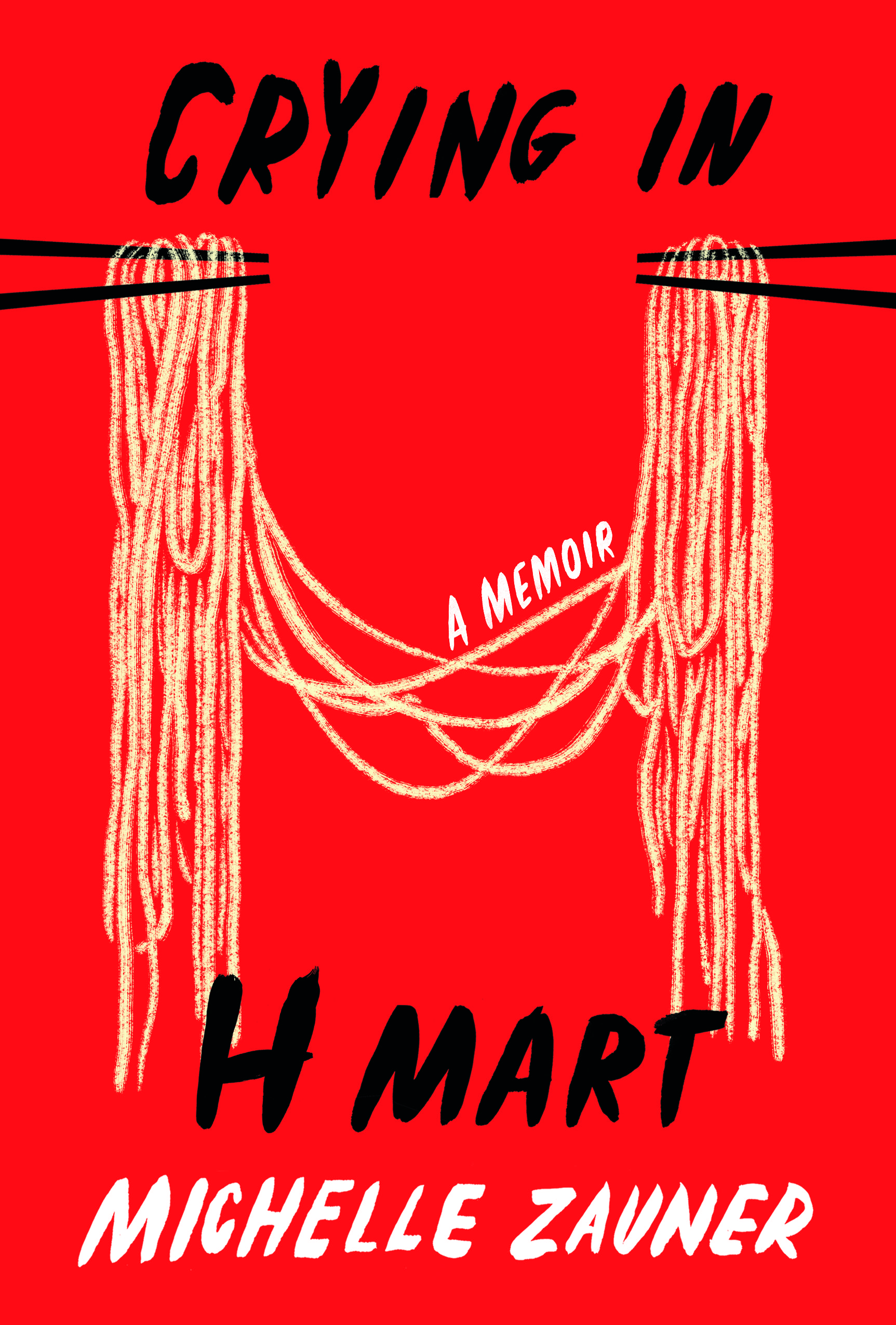

I am recommending—imploring, really—that you read Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart. I would be lying if I said I didn’t usually avoid books about terminal illness (a lesson learned after spending all of my eighth-grade year mourning Tuesdays with Morrie and later, an entire summer bruised by Just Kids), but I’m a long-standing Japanese Breakfast fan so I broke the pattern for Zauner.

I’ve never been made at once so hungry and so depressed by a book in my life. The memoir is flush with descriptions of Korean dishes: tangsuyuk (sweet-and-sour orange pork), jjajangmyeon (black bean noodles), sannakji (live long-armed octopus) and a hundred others, all of them variously detailed in smell, texture, and taste. After her mother is diagnosed with stage IV squamous-cell carcinoma, we see Zauner navigate Korean recipes and traditions in an attempt to nurse her mother back to health, or at least to demonstrate her love, her loyalty, and an acute remembrance of her mother’s life. Zauner confronts the difficult realities of mortality and identity as the encroaching illness of her mother makes her reexamine her own Korean heritage.

It rivals—can I say this?—Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking in its emotional intelligence and sincerity. It feels educational, deeply insightful with its lessons on love and attention, like here, when she describes her wedding vows: “I talked about how love was an action, an instinct, a response roused by unplanned moments and small gestures, an inconvenience in someone else’s favor.”

Crying in H Mart has become my new, comprehensive recommendation for a book on death and identity, just as Zauner’s songs “Till Death” and “Boyish” are my stalwart song recommendations for the same. And while I’m recommending things, or more precisely fan-girling, I’ll suggest listening to Michelle Zauner’s new album, too—Jubilee. The first track, “Paprika,” is a top 10 of the decade for me.

— Julia Harrison, Editorial Assistant

You can order many of these titles through your local independent bookstore or by shopping through Bookshop.org, which supports local bookstores with every purchase.

We also highly recommend subscribing to the Sewanee Review. New subscriptions will begin with our forthcoming summer issue, which features returning contributors Jen Logan Meyer, Michael Robbins, and Lea Carpenter, as well as—for the first time in the magazine—Emily Jungmin Yoon, Katie Moulton, Buku Sarkar, and Kwame Dawes. We hope you’ll subscribe.