For our newest weekly web feature, Stanzas, we ask writers to introduce us to their favorite poets by way of a handful of poetic lines. For the inaugural Stanzas feature, poet and critic Ange Mlinko, whose poems appear in our Winter 2019 issue, meditates on a stanza by one of her favorite poets, Joseph Brodsky.

The piazza’s deserted, the quays abandoned.

The café walls are more crowded than the café inside:

a lute’s being strummed by a frescoed, bejeweled maiden

to her similarly decked Said.

Oh, nineteenth century! oh, lure of the East! and oh, clifftop poses

of exiles! and, like leukocytes in the blood,

full moons in the works of bards burning with tuberculosis,

claiming it is with love.

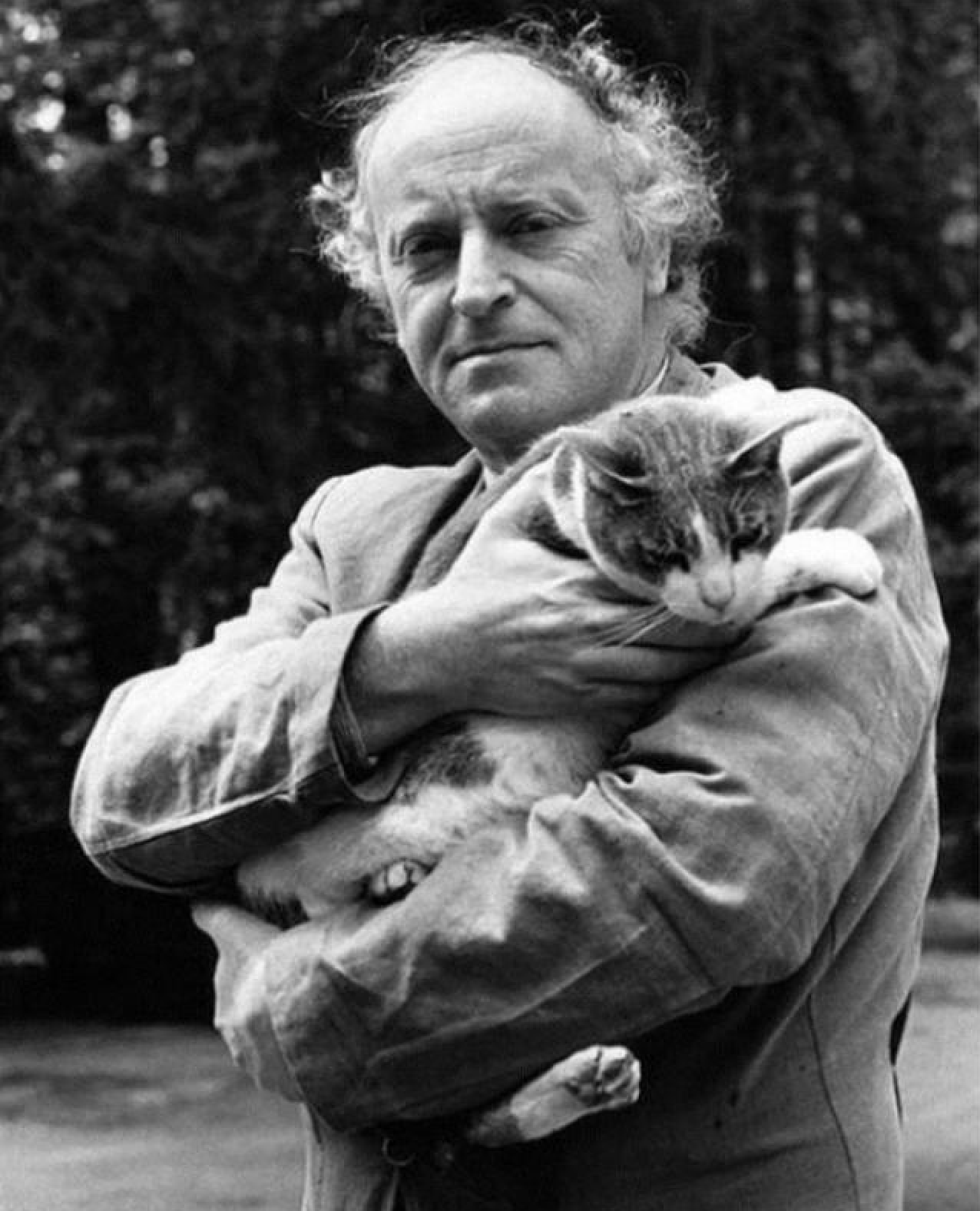

When I was an adolescent, knowing next to nothing except what I liked, two of Joseph Brodsky’s poems got their hooks into me, “Belfast Tune” and “October Tune.” Both appeared in The New Yorker in separate issues in 1987. (God knows how I had come across The New Yorker—it certainly never darkened my parents’ doorstep.) They were memorable for being different from the usual fare, and what distinguished them was their rhyming stanza forms. Already that had become a forbidden pleasure.

We were lucky to have Joseph Brodsky as an American poet for a while; his subversive use of stanzas remains key. I had a real devil of a time settling on which one to single out, but for its characteristic mixture of gorgeousness and disenchantment I chose the second stanza of “Venetian Stanzas I,” which like all of his winter-in-Venice poems, celebrates its beauty while acknowledging beauty as an optical illusion.

As I tell my students, if you want to visit Italy you have to book a stanza. I love the unenjambed stanza, the self-sufficiency of it, and like a well-designed room, Brodsky’s always has a focal point: in this case, the shocking metaphor of full moon as leukocyte (perhaps that moon also means that stanzas have windows; one looks out of them as well as into them). Even as he invokes romanticism (that declamatory oh, those exclamation points), he won’t exclude the TB. He thus injects twentieth-century urban realism into a city that still barely admits automobiles. Who can resist such melancholy wit?

Looking at stanzas in a foreign alphabet, like Russian, is a reminder of the inherent beauty of the form as it patterns the blank page. That too is an optical illusion—it tells you nothing of the quality of thought in that foreign language—but it’s a start; it makes you want to know. And then, reading a perfect specimen that has flounces and sternness, ornament and irony, you want to read on. One stanza is never enough.