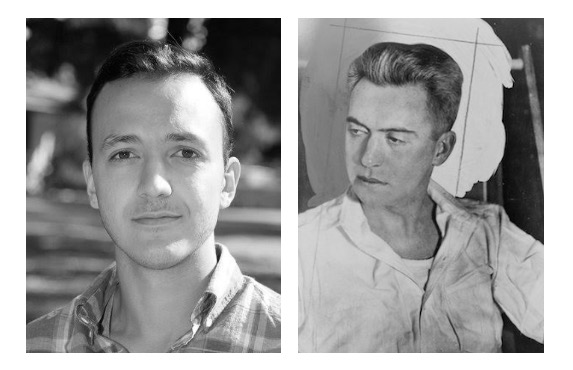

For our Stanzas web feature, we ask writers to introduce us to their favorite poets by way of a handful of poetic lines. This week, Armen Davoudian, whose poem "The Palace of Forty Pillars" appeared in our Summer 2019 issue, examines the opening stanza from "To Brooklyn Bridge" by Hart Crane.

With some poems, sustained analysis and repeated readings do not so much deepen one’s understanding as illuminate the depths into which one fell on that first reading. I first came across a copy of Hart Crane’s The Bridge in the Spring of 2008, in the Austrian Public Library in Vienna, where my family and I were awaiting our immigration papers en route from Iran to the U.S. With little German and only slightly more English, I blissfully attributed Crane’s difficulty to my own lack of linguistic fluency.

At the time, I didn’t know what a Linzer torte was made of, but I liked the taste. Explaining his early attraction to “poets in languages in which I was unskilled,” T. S. Eliot argued that “genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.” But communicate how?

How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull's wings shall dip and pivot him,

Shedding white rings of tumult, building high

Over the chained bay waters Liberty—

By way of assonance and near-assonance (how and dawn; white and high; chained and bay; chill, his, rippling, dip, pivot, him, building, rings, Liberty), alliteration and off-rhyme (ripple, rest; dip, pivot; chill, gull, shall; white, tumult). Before—and in Crane’s case, long before—a poem makes sense, it makes music. That trochaic inversion in the first line, coming right after the caesura (CHILL from), is perfectly placed to send a chill down the reader’s spine.

The not-yet-quite-understood poem also communicates by way of syntax, which may bring us closer to sense than sound did, but still stands apart. We might find ourselves compelled by the syntactic gesture of a sentence before we have quite grasped its meaning. “How many,” Crane’s poem asks, and we know we’re in the middle of a question—only to end up with a dash at the end of the quatrain. That dash occupies the elusive brief interval between incredulity (which is shaded by wonder) and disbelief (which is shaded by doubt), between the exclamation point and the question mark: How many dawns? So many dawns!

The ambiguous (or is it ambivalent?) dash allows the sentence to slide from question to exclamation, but that’s hardly the end of it. “Then, with inviolate curve, forsake our eyes,” begins the next quatrain. The actual syntax is still one of question-exclamation: How many dawns shall the seagull’s wings . . . forsake our eyes!? But at this point we’re so far from the interrogative adverb (“How”) which launched the question that we’re more likely to read “And then, forsake our eyes” as an independent clause in the imperative mood, which is also the mood of the poetic ode, and the mood of prayer. A master of syntactic delay, Crane models how the mind begins in curiosity, is rocked by doubt, resolves in wonder, and is moved to praise.