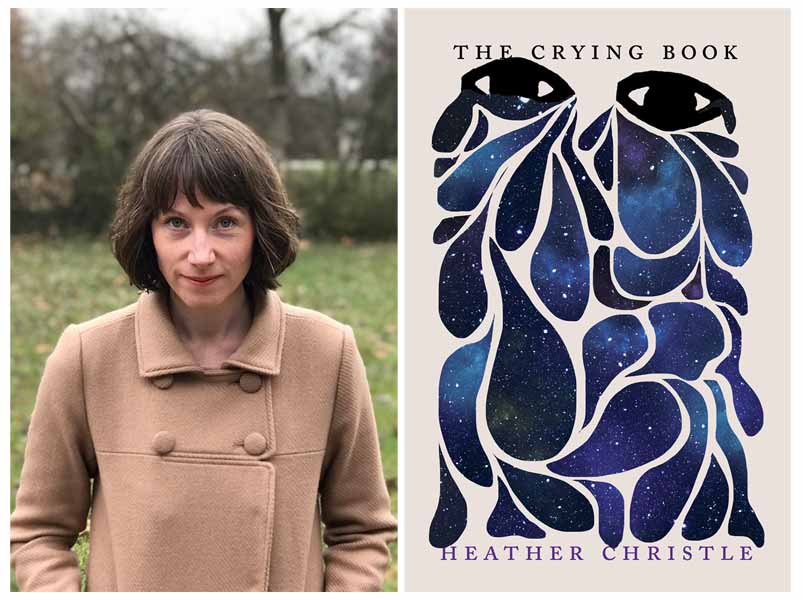

The Review was honored to catch up with poet and memoirist Heather Christle—whose poem “64 Fouettés” appears in our Spring 2020 issue—to talk about the consequences of a “nightless future” and her most recent publication, The Crying Book. In addition to The Crying Book, Christle is the author of four poetry collections, including Heliopause and What Is Amazing, published in 2015 and 2012 respectively.

— Jennie Vite

SR: Your poem “64 Fouettés” begins with a cat who “makes a sound I do not recognize as his,” which acts as a catalyst for the speaker’s meditation. I noticed that something similar happens in The Crying Book, where you observe how “people often mistake the cries of a cat for those of an infant.” What do you make of these affinities with animals and their noises? Is it easily explained away by saying you’re a cat person, or is there something more?

Christle: I have lived with a cat and at least one other human for all but six months of the past thirteen-and-a-half years. They are the only animate beings I live with, and so they seem much riper for connection and comparison than say, a human and the bathroom sink faucet. (The latter of which I’ve lived with for even more of my life.)

SR: Your poem builds to an apocalyptic revelation: “He will pay for this at Trivia Night if he makes it to the future // (if the future still has trivia, if the future still has night).” What does it mean to have a nightless future? I also wonder if this line takes on for you any additional significance in our current moment.

Christle: Oh my god, yes. This is true of so many poems at the moment, I think. The poems I wrote in this complete-sentence-as-line form (of which there are many!) often were doing the work of inhabiting an uneasy future, or anticipating it. There’s another one from this era that ends “Then I will float on to look for some people / And there are no more people / Where have the people all gone,” which now feels . . . very familiar.

But coming back to a nightless future—I’m not sure exactly what it would mean. The poem is an invitation to imagine that, which I arrived at simply by following the logic established with the more immediately comprehensible “if the future still has trivia.” In the poem’s mind, if this phrase must be uttered about the first word in “trivia night,” then it’s only fair and reasonable to keep going. And I know that when I reached that realization I felt that a trap door had opened beneath me, which is often for me a sign that I am (or the poem is) done.

SR: The Crying Book, your first book of prose, possesses a musical quality—it has been described as “symphonic.” Is your prose writing informed by your poetry practice? How did writing The Crying Book change your writing process?

Christle: Both modes require (for me) an ability to allow unexpected correspondences to emerge, not forcing them, but happening upon them through the act of writing. (I love the word “happen” very much.) And the time I have spent writing poems has given me a pretty strong sense of when a line rings true or falls flat. I try to bring that attention to prose as well. (At the same time, when I was revising The Crying Book I sometimes sang a little Joanna Newsom to myself: “Never get so attached to a poem / you forget truth that lacks lyricism.”

Moving back to writing poems after finishing an early draft of The Crying Book was an enormous relief, because the associative movements were not ones I had to balance in this enormous system. Or here is a better way to say it: when I am writing nonfiction prose I feel like I am simultaneously climbing and building a mountain. When I am writing poems I feel like I am throwing myself off a cliff. The difficulty is I have to let myself really fall. If I fake it the poem becomes inert.